Venture capital (VC) has undergone a seismic shift over the past two decades, evolving from a niche cottage industry into a complex, fragmented asset class with multiple sub-strategies (seed, early-stage, growth, multi-stage, etc.). At the same time, capital inflows have surged from family offices and other new entrants seeking to increase exposure to the innovation economy. According to Deloitte, the number of family offices has grown from 6,130 in 2019 to 8,030 in 2024, with projections reaching nearly 11,000 by 2030. Similarly, aggregate family office AUM is expected to grow from $5.5 trillion today to $9.5 trillion in 2030, a massive $4 trillion increase in just the next five years! As more family offices and institutions consider allocating to VC, they face a fundamental question: Do we build it or buy it?

Despite the many benefits of venture funds of funds (FoFs), skepticism persists. As a career-long allocator, I was once skeptical myself—until I took a first-principles approach to examining the root of this hesitancy. Below, I address the most common concerns and misconceptions about FoFs—and why many LPs should rethink their stance.

Here are the most common objections to FoFs I hear from LPs:

The "Double Layer of Fees" Concern: Many LPs assume that FoFs underperform due to additional fees without ever doing the work to test this assumption.

Career Risk: Some LPs fear that investing in a FoF signals an inability to execute a direct VC strategy, potentially jeopardizing their own roles.

Institutional Rules Against FoFs: Many institutions have a blanket “we don’t do FoF” policy—often inherited from prior leadership regimes—without ever critically assessing whether the rule makes sense.

The Appeal of Direct VC Fund Investing: Venture is an exciting asset class—startups are building rockets, robots, AI models, and discovering new therapeutics. Many LPs enjoy direct VC investing for the experience, networking, and status, even if it’s not their most effective approach. Simply put, it’s fun.

Before addressing these objections, let’s establish two fundamental truths about VC:

Venture is an "Access Class": The best funds and deals are access and capacity-constrained. While most LPs recognize that premier firms like Sequoia, Benchmark, and USV are difficult to access, the top emerging funds can be just as exclusive (and sometimes even harder to get into due to their small size). Without strong networks built over long periods of time, LPs won’t have access to the best deals and, therefore, risk adverse selection.

Venture Investing Requires Intense Effort: The best VCs strive to see every deal and are critical of even a single missed opportunity. Shouldn't the best LPs apply the same level of rigor? Unless you are one of the few fortunate LPs that has access to the very few undeniably premier firms like Sequoia, Benchmark, and USV, finding the next breakout firm requires sifting through thousands of venture funds. Yet, many LPs meet only a handful of funds each year and rely on reactive sourcing. This approach is inherently limiting and, to a large extent, arbitrary relative to the scope of one’s network. Evaluating any single fund in a vacuum is futile. Without seeing a large part of the total universe and forming a baseline of quality, it’s impossible to appropriately contextualize any single fund. However, this takes significant time and effort that amounts to a full-time job if done correctly. Additionally, the rapid pace of innovation and change within the technology sphere means that even more time and expertise is required to continue to monitor the latest trends and remain up to speed on one of the most dynamic asset classes today.

Now that we’ve established these two truths, let’s revisit the reasons why most LPs dismiss FoFs:

Myth #1: FoFs Underperform Due to Double Fees

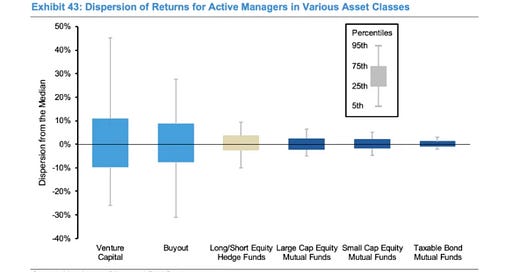

This concern is actually valid for many FoF strategies in other asset classes, particularly within the hedge fund world where return dispersion is much narrower (meaning there is not a big difference between top quartile, median, or bottom quartile returns). Lower return dispersion means double fees can often erode any excess returns simply because the “excess” is not as large. Because of this dynamic, many LPs believe that all FoF strategies are bad and will underperform.

But venture is different. The return dispersion is massive. The chart below shows return dispersion for active managers across various asset classes. It’s clear that the return dispersion in venture is significantly wider than any other asset class. The top 5% of venture funds outperform median funds by ~45%, compared to just ~10% for hedge funds. A fund of hedge funds that is able to access top-performing managers will likely see its outperformance eaten away by the double layer of fees. On the other hand, if a venture FoF is able to access top-performing managers, the sheer magnitude of the outperformance should be so large that the double layer of fees won’t significantly erode excess returns.

To validate this further, I analyzed PitchBook performance benchmarking data from 2005-2019, comparing net TVPI for the entire VC universe (we’ll call this “direct VC”) versus VC FoFs. Interestingly, the VC FoF universe broadly outperformed the direct VC universe, even net of the double layer of FoF fees (all data I examined is net TVPI, which accounts for all fees, including the double layer of fees for FoFs). I’ve included the raw data below (the bolded figures represent outperformance vs. the same vintage and quartile figure for the other data set):

Top quartile: FoFs outperformed direct VC in 8 of 15 vintages, with an average outperformance of 0.27x TVPI.

Median quartile: FoFs outperformed direct VC in 14 of 15 vintages by an average of 0.68x TVPI.

Bottom quartile: FoFs outperformed direct VC in every vintage by an average of 0.89x TVPI. Notably, the bottom quartile for FoFs was still above 1x (and often meaningfully so) for every vintage we looked at, highlighting the downside protection FoFs offer by avoiding low-quality managers.

Reduced risk: VC FoFs had significantly lower return dispersion—on average, just a 0.58x spread between top and bottom quartiles versus 1.21x for direct VC.

This data clearly refutes the notion that FoFs inherently underperform – in fact, the data shows that FoFs actually outperform the broader venture universe, even net of the double layer of fees, all while providing more consistent returns.

Myth #2: Investing in a FoF Signals Weakness

Many LPs are generalists, covering multiple asset classes beyond venture, including public markets, credit, and real estate. Even among private market specialists, venture is often just one part of their overall mandate. There are very few LP settings that allow for a dedicated VC resource (large institutions with deep pockets and massive teams are the exceptions). Given the time-intensive nature of venture investing, most allocators lack the appropriate bandwidth to execute a best-in-class strategy on their own.

Rather than signaling a lack of competence, partnering with a specialist FoF demonstrates self-awareness and a desire to put performance over ego. The allocator community readily embraces and advocates for specialist managers across asset classes—so why are LPs themselves expected to be generalists?

Myth #3: "We Don't Do FoFs" Is a Valid Rule

Many institutions have long-standing policies against FoFs, often inherited without reconsideration. I’ve worked inside these types of institutions and, at one point, fully subscribed to this narrative. However, once I started to question the rationale (or lack thereof) behind these policies and came to understand the benefits of FoFs, I changed my mind, and ultimately decided to cross over to the “dark side” to join a FoF.

When pressed, many of these LPs often cite fees or the belief that they shouldn’t “outsource their job.” However, few take the time to rigorously evaluate the benefits of FoFs or the opportunity cost of attempting to replicate the strategy in-house. Blanket rejection is often more dogma than data-driven or intellectually honest decision-making.

Myth #4: FoFs Take the "Fun" Out of VC

It’s true—venture is exciting. Many LPs want to try their hands at venture, not just for financial returns but for the thrill of engaging with exciting startups, attending AGMs in fun locations, getting cool swag, and networking with notable founders and investors, regardless of whether or not they are qualified or if the time spent even makes sense relative to the quantum of capital deployed. Human psychology often prevails in the face of reason. These behaviors are driven purely by the id, even as the ego hesitates and the superego sounds alarm bells.

While a FoF may seem like a step removed from the action, the best FoFs create experiences for LPs. For example, at Pattern, we regularly host GP/LP events and facilitate direct introductions between our LPs and managers. In fact, if our LPs want to invest in some of our portfolio GPs directly, we view this as mutually beneficial and a strong sign that our strategy is working.

Additional Overlooked Benefits of FoFs

Beyond superior access and risk-adjusted returns, FoFs offer practical advantages, particularly for smaller LPs:

Vintage diversification: Venture returns are cyclical, but it's nearly impossible to predict strong vs. weak vintages in real-time (no matter how obvious it may seem at the time). The most sensible strategy for most LPs is to steadily deploy capital each year. Yet this proves difficult because of fear and greed: they end up investing more when the market is hot late in the cycle and less when valuations are cooler early on—despite knowing they should do the opposite. A LinkedIn post that I recently read succinctly captured this dynamic. A FoF naturally provides vintage year diversification because it and its underlying managers deploy capital over multiple years, often resulting in exposure across 4-5 vintages. This structure frees LPs from committing capital annually and offers a streamlined way to achieve consistent, diversified venture exposure with a single commitment.

Cost-effectiveness: We previously detailed the time intensity required to successfully execute a venture strategy and established that it’s a full-time job. Hiring an in-house venture specialist can easily cost at least $250K annually, and even then, you’re getting a single person whereas a FoF provides access to a team of experts with broader capabilities. For many LPs, paying a 1% management fee to a FoF is often cheaper, more effective, and often gets you access to a full team of experts that can act as an extension of your in-house team.

Time efficiency: Building a diversified portfolio of venture capital funds takes a LOT of time, and that time can cost organizations a lot of money. With one single diligence process, an LP can allocate to a FoF and get sufficient diversification. In order to attain this same level and quality of diversification without using a FoF, one would have to invest thousands of hours to meet with hundreds of managers, conduct extensive deep due diligence on each high quality prospect, and ultimately make dozens of individual investment decisions.

Operational efficiency: Managing multiple direct VC investments involves frequent capital calls, disparate reporting portals, and numerous K-1s, which can present a hefty operational burden for smaller and less sophisticated investors. A FoF streamlines this with one single stream of cash flows, aggregated reporting, and one single K-1.

Conclusion

VC is one of the most challenging asset classes to execute well—it requires deep networks, significant time investment, and access to the right funds. Yet many LPs attempt to build direct VC portfolios despite being spread thin, lacking the bandwidth to meet enough funds, and facing adverse selection.

Venture FoFs offer a streamlined alternative, often providing better access, superior diversification, and historically strong net performance—despite the additional fees. They also provide the benefits of operational efficiencies, downside protection, and vintage year diversification.

The skepticism toward FoFs often stems from outdated biases, misconceptions, or the association of FoFs with other asset classes where the strategy isn’t as effective. But the data tells a different story for VC FoFs. For LPs serious about optimizing their venture strategy, the data is clear: it’s time to rethink FoFs.

really great article... only criticism is that i think you buried the lede here.

your title / headline for this post should be something like "VC FoF outperforms traditional VC fund investing, EVEN WITH A DOUBLE LAYER OF FEES" ;)

A really well-written piece. I don't think most LPs even realize how much the median/top quartile FoF outperform. Those side-by-side charts are definitely worth calling more attention to